...unless you expect your software to never change—which, let's be honest, is never the case.

This statement reveals a fundamental truth about software development that connects two seemingly different disciplines: software design and agile methodologies. Both exist to solve the same underlying problem, yet they're often treated as separate concerns.

When Design Becomes Essential

Imagine building an application with perfect, complete requirements. Imagine those requirements never changing—not once, not ever. In this scenario, design truly doesn't matter. You could hardcode values, tangle dependencies, and build the messiest structures imaginable. The application would work flawlessly because it would never need to adapt.

But this world doesn't exist.

Change as the Driving Force

Change is the universal constant that makes both design and agile practices essential. It's the force that transforms well-intentioned code into legacy systems and careful plans into historical artifacts.

When requirements shift—and they always do—poorly designed systems become mazes. Developers spend more time deciphering existing code than building new features. Simple modifications require understanding intricate webs of dependencies. What should take hours takes weeks.

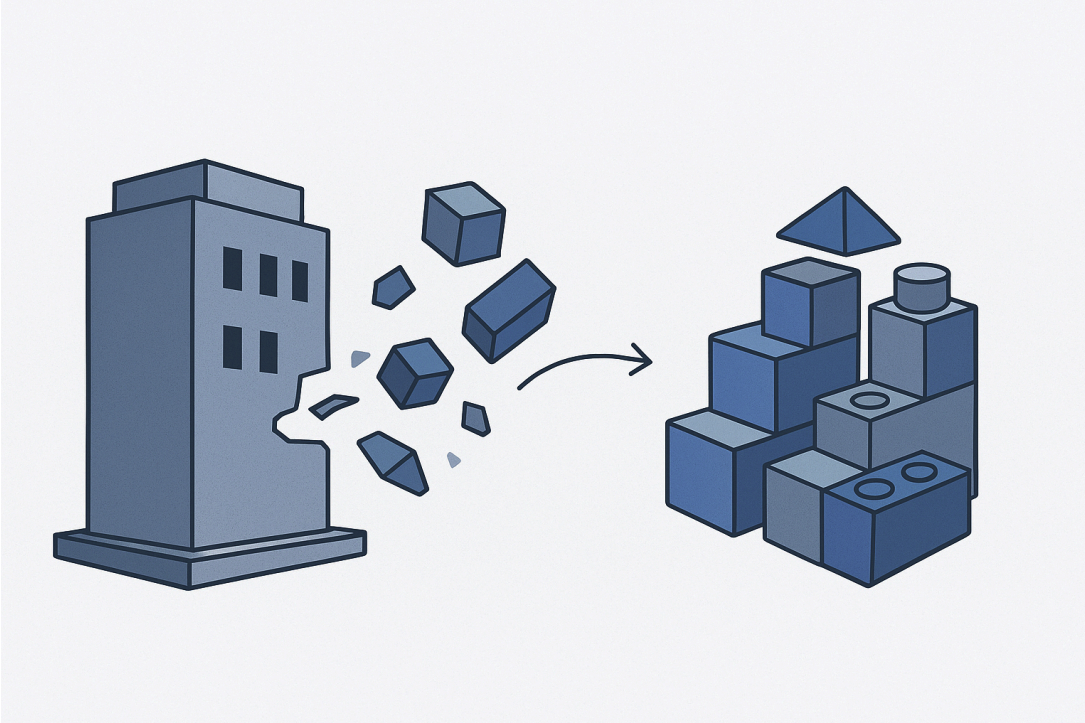

This is precisely where thoughtful design pays off. Clean abstractions allow modifications to ripple through systems predictably. Well-defined interfaces contain changes to specific boundaries. Modular architectures enable isolated updates without system-wide repercussions.

The Agile Connection

Agile methodologies emerged from the same recognition: change is inevitable, so we must structure our processes to embrace it rather than resist it. Traditional waterfall approaches assumed we could gather complete requirements upfront and execute against them linearly. Agile acknowledges that understanding evolves alongside implementation.

The connection becomes clear when you consider that agile practices are essentially process-level design patterns. Iterative development creates feedback loops that catch misalignment early. Sprint planning provides natural boundaries for scope management. Retrospectives function as refactoring sessions for team processes.

Both design and agile methodologies share a common philosophy: build systems—whether code systems or development systems—that can absorb change gracefully.

The Symbiotic Relationship

This isn't coincidental. Well-designed software enables agile practices, while agile practices demand well-designed software.

I've experienced this friction firsthand. On a project early in my career, we were working with a codebase where everything was tightly coupled - database logic mixed with business rules, UI components directly accessing data stores, and configuration hardcoded throughout the system. When stakeholders requested what seemed like a simple feature change during a sprint, we discovered it would require modifications across dozens of files.

What should have been a two-day task became a three-week refactoring nightmare. Our sprint commitments became meaningless because we couldn't predict how any change would ripple through the system. The agile process broke down entirely - we couldn't deliver incrementally, couldn't gather feedback quickly, and couldn't pivot when priorities shifted.

Conversely, I've worked on systems built with change in mind where agile workflows felt natural. Features could be developed incrementally. Refactoring became routine rather than risky. Experimentation was possible because changes could be isolated and reversed.

The Practical Implication

Understanding this connection changes how we approach both design and process decisions. Design isn't about building the most elegant solution for today's problems—it's about building a foundation that can evolve with tomorrow's challenges. Agile isn't about following a methodology blindly—it's about creating conditions where software and teams can adapt effectively.

This doesn't mean over-engineering or creating abstractions prematurely. Rather, it's about making conscious decisions that balance immediate delivery with future flexibility. Sometimes the right choice is to keep things simple now and refactor later when changes actually emerge. The key is being intentional about these trade-offs rather than ignoring them entirely.

The next time you're balancing quality and delivery speed, ask yourself: will this decision make it easier or harder to adapt when requirements inevitably change? Because they will change—and when they do, you'll either thank your past self for the foresight, or curse them for the shortcuts.

Change isn't the enemy of good software—it's the reason good software matters.

.png)